- Vocally Protective Anesthesia - August 7, 2018

Vocally Protective Anesthesia

What is it?

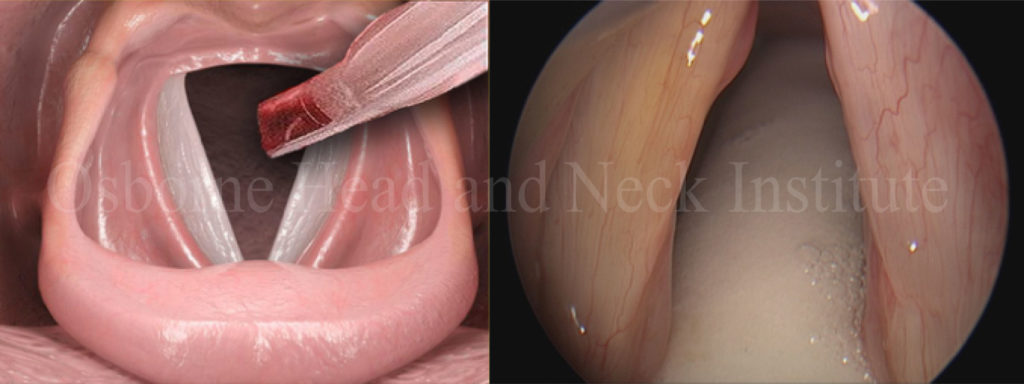

An anesthetist’s most vital skill is their ability to manage an airway. This requires having a complete understanding of airway anatomy. Without this knowledge and attention to detail, structures such as the vocal cords could become temporarily or permanently injured. The airway, specifically the larynx (voice box), is responsible for many important tasks and injury can cause changes in the patient’s ability to swallow, phonate (produce voice), and breathe. At Osborne Head and Neck Institute (OHNI), the Division of Anesthesia has collaborated with the Division of Voice to develop the most protective protocols that exist in anesthesia.

James Sherer, the lead anesthetist at OHNI, has worked with Dr. Gupta to develop a sophisticated understanding of the larynx, voiced sound, resonance, and articulation. He has translated this knowledge into airway management protocols that are safer for the larynx. This has resulted in refinements in equipment selection, medication administration, and airway management techniques through all phases of the surgical process.

Why is it important?

Most head and neck surgery involves intubation with a soft, plastic tube called an endotracheal tube. These tubes come in different shapes, sizes, and material compositions. These tubes are inserted using a device that permits visualization of the entire airway to identify where the tube should go and what to avoid. After placement, a small balloon-like cuff located near the end of the tube is inflated to allow mechanical ventilation (a machine breathing for you during surgery). Procedures involving the head and neck typically require the patient’s face, including the endotracheal tube, to be completely covered with a sterile, surgical drape. This necessary step hinders direct visualization of the tube during the procedure. After surgery, the endotracheal tube is removed before waking the patient.

Any of these steps could result in an injury, which could compromise voice quality or breathing. An anesthesia provider must understand the possibility of injury at each step, how it might occur, how it could be prevented, and what to do if complications arise.

What are my options?

All patients should demand the highest level of care possible from their anesthetist. Aside from basic knowledge of intubation and extubation, a provider must understand how to avoid complications. This permits the patient to return to their regular routine sooner after surgery. In particular, the career and livelihood of a professional voice user is at risk during any procedure that requires an endotracheal tube. Maintaining the integrity of the voice must be one of the highest priorities.

At Osborne Head and Neck Institute, protocols were developed to minimize the risk of injury from anesthesia. These modalities, can be career-saving for the professional voice user, are universally applied to ensure every patient gets the best airway care. All patients deserve this level of care.

It is important that you speak with your anesthesia provider about your concerns and that you are comfortable with the information you receive. You may consider questions such as:

- Do you work with (your surgeon’s name) often?

- Have you provided anesthesia for many professional voice users?

- Could there be any injury to my voice from managing my airway?

- Can anything be done differently to protect the integrity of my voice?

- If I notice a change in my voice after surgery, who should I speak with?

Unfortunately, in most settings, you will not speak with your anesthesia provider until the day of surgery. In those cases, ask your surgeon if they know who will be doing your anesthesia. These questions will help you gain a sense of the relationship they have with their anesthetist.

A consistent team approach is always best when it comes to your surgery and having a surgical team comprised of surgeon, anesthesia, surgical technicians, and surgical nurses who frequently work together will increase your chances of having the best possible outcome for your procedure.

To learn more about vocally protective anesthesia, please visit: www.ohni.org